Strange as it seems, as late as the summer of 1973, Paul McCartney was still trying to find his musical footing in a post-Beatles world. Each of his four solo album, including two made with his band Wings, had featured superb moments, but none had matched the high standard set by his work with the Fab Four. His fifth album, Band on the Run, changed all that. Brilliant from start to finish, the album freed McCartney from the long shadow of the Beatles’ legacy, and helped give the beloved artist a new musical identity. But it didn’t come easy.

The monumental troubles that plagued McCartney and Wings during the making of Band on the Run could easily serve as fodder for a Hollywood film epic. The difficulties originated with McCartney’s desire to work in an exotic environment, far off the beaten path. His record company, EMI, had an international presence, with recording facilities based in Bombay, Rio de Janeiro, Peking and the Nigerian city of Lagos. Enchanted by visions of sunning on the beach by day and recording by night, McCartney opted for the African locale, nestled on that continent’s west coast.

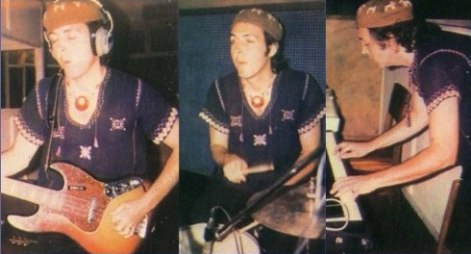

Booking studio time in Lagos for September, the former Beatle first gathered his fellow Wings bandmates together for some rehearsal work in Scotland. Tensions ensued, and just one week prior to departure, guitarist Henry McCullough and drummer Denny Seiwell resigned from the group. Wings was suddenly down to just three members: McCartney, his wife Linda and guitarist Denny Laine. Undeterred, McCartney opted to forge ahead with the original recording plans.

Booking studio time in Lagos for September, the former Beatle first gathered his fellow Wings bandmates together for some rehearsal work in Scotland. Tensions ensued, and just one week prior to departure, guitarist Henry McCullough and drummer Denny Seiwell resigned from the group. Wings was suddenly down to just three members: McCartney, his wife Linda and guitarist Denny Laine. Undeterred, McCartney opted to forge ahead with the original recording plans.

“That was like a bombshell,” the former Beatle later told Clash Music, recalling the defections. “It was like, ‘Ah, OK. Try and hold your nerve, try and keep it together.’ At that moment [I thought], ‘I’ll show you. I will make the best album I’ve ever made now.’”

Arriving in Lagos, the trio discovered that the EMI studio was in serious disrepair. Microphones had been stashed away in a cupboard, the mixing board was faulty and acoustic baffles used for sound separation were nowhere to be found. Heroically, engineer Geoff Emerick pulled together the necessary equipment to push ahead.

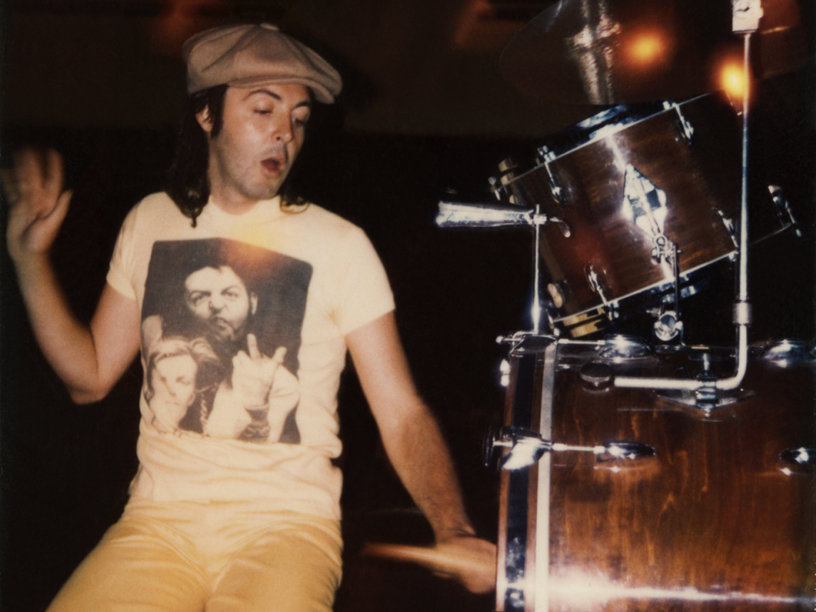

Soon enough, a daily routine was established. Weekday mornings were spent swimming at a local country club, while afternoons saw the band making the hour-long drive to the recording facility, where work often lasted until the wee hours of the morning. Weekends were reserved for rest and recreation, in keeping with McCartney’s reasons for choosing to record in Lagos in the first place.

Throughout the sessions, McCartney, Linda and Laine remained galvanized and motivated by the defections of Seiwell and McCullough. McCartney himself assumed most of the lead guitar and drumming duties, reprising the roles he had often taken on his previous solo albums. Notwithstanding the technical difficulties, recording was moving along relatively smoothly until one evening when the McCartneys decided to take a leisurely stroll. Seemingly out of nowhere, a car shot up beside them, five men jumped out and, at knifepoint, McCartney was forced to relinquish all valuables in his possession. Among the items taken were cassettes of demo recordings of potential material for the new album.

“It was all the stuff we did,” McCartney later recalled. “The tapes [contained] the original demo of ‘Band on the Run.’ If [the thieves] had known, they could have held onto them and made themselves a little fortune. But they didn’t know, and we reckoned they would probably record over them.”

Such was the first in a series of ongoing travails. On another occasion, McCartney collapsed in the studio, unable to catch his breath. He feared he was suffering a heart attack, but after a period of rest he managed to gather himself. The episode was later diagnosed as a bronchial spasm triggered by excessive smoking. In another odd incident, a local Afro-beat star and political activist went on radio and accused McCartney of traveling to Lagos to “exploit and steal” African music. To placate the accuser, McCartney agreed not to enlist help from local musicians. He also steered clear of giving any songs an “African” sound.

By the end of September, six weeks into their stay, the Wings entourage was relieved to be headed back to London. Overdubs to the Lagos recordings were added at Air Studios, including terrific orchestral arrangements by Tony Visconti, best known for his production work with Marc Bolan and David Bowie. On October 28, the iconic album cover photo—featuring actors Christopher Lee and James Coburn, among other celebrities—was shot.

Incredibly, despite the harrowing incidents that had occurred in Lagos, the finished album brimmed with a buoyant spirit. Its brilliance is evident from the start in the title track, a three-part suite that segued beautifully from a languid intro to a stuttering midsection, before giving way to a strummed acoustic guitar that heralded a jaunty, deliciously melodic mid-tempo finale.

Other high points included “Jet,” a power pop anthem that was rightly chosen as the album’s first single; and “Bluebird,” a plaintive acoustic gem that ranks among McCartney’s best loved ballads. The album had its angular moments as well, particularly with “Let Me Roll it,” a bluesy Lennon-like shuffle fitted with a brittle guitar figure and tape-echo applied to McCartney’s vocals. All four of those numbers still occupy a covered spot in McCartney’s regular concert set lists.

Not surprisingly, Band on the Run went on to become the most beloved album of McCartney’s post-Beatles career, a status it enjoys to this day. Its legacy was evident in its commercial success, as it became the top-selling studio album of 1974 in the U.K., and topped the Billboard 200 album chart in the U.S. Most importantly, the record established a musical identity for McCartney and Wings—an overarching style that blended McCartney’s pop smarts with deft arrangements—that carried forward in the band’s future work.

Not surprisingly, Band on the Run went on to become the most beloved album of McCartney’s post-Beatles career, a status it enjoys to this day. Its legacy was evident in its commercial success, as it became the top-selling studio album of 1974 in the U.K., and topped the Billboard 200 album chart in the U.S. Most importantly, the record established a musical identity for McCartney and Wings—an overarching style that blended McCartney’s pop smarts with deft arrangements—that carried forward in the band’s future work.

“I think we just became a better band,” McCartney told Clash Music. “I figured out what I had been trying to work out, which was, ‘What was the Wings sound?’” He added, “You start off imitating people and just goofing around, trying to find out what works and what doesn’t work. [With] things like ‘Band on the Run’ and ‘Jet’ and ‘Let Me Roll It,’ we suddenly found songs that people identified with.”

Even John Lennon, who generally only grudgingly complimented McCartney’s post-Beatles work, was forced to concede that his former partner had achieved something special. “Band on the Run is a great album,” he told Rolling Stone, not long after the record was released. “Wings keep changing all the time, [but] it doesn’t matter who’s playing. You can call them Wings, but it’s Paul McCartney music—and it’s good stuff.”

Paul McCartney has plenty of 2019 tour dates. Tickets are available here and here.

bestclassicbands