Pete Best talks about picking yourself up and getting on with it

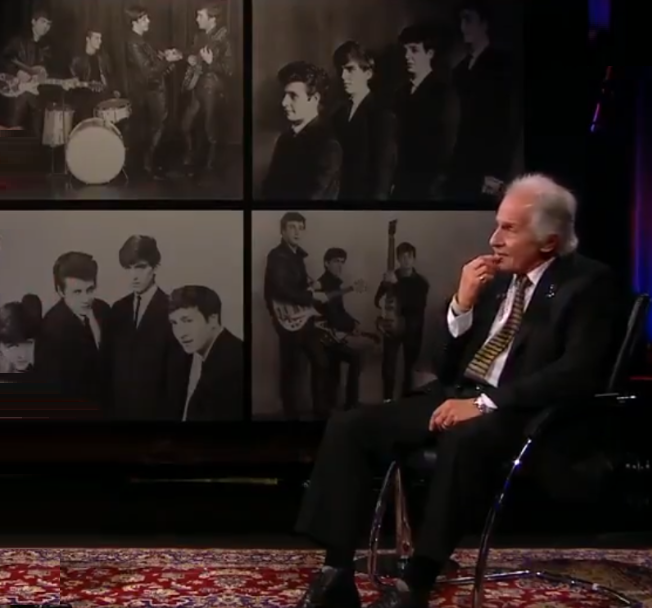

Drummer Pete Best is explaining, not for the first time, what it was like for him that late summer’s day in 1962 when he was sacked suddenly from The Beatles, a beat combo from Liverpool who were about to become the biggest band the world had ever seen.

Best recalls an uncomfortable-looking band manager Brian Epstein explaining that other band members John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison didn’t think his drumming was up to scratch, and that they were replacing Best – who’d been with them for two years through those formative, frenetic Hamburg gigging days – with Ringo Starr.

“We were rockers, we were little hardies, we could handle ourselves. But when I got back home and I told my mother what happened, behind the sanctuary of the front door, I cried like a baby,” he recalls.

Anybody over a certain age who hears the name Pete Best will be familiar with the saga of the so-called “fifth Beatle” and the life he lost out on. Rather aptly, we meet in Lost Lane, a music venue off Grafton Street, where he was due to play a gig on March 29th, now cancelled due to the Covid-19 crisis. But as soon as we start talking, it’s clear that despite the events of 1962 he doesn’t feel lost, and hasn’t for a very long time. He’s 78 now, and looks back with pride not just on his part in Beatle history, but his resilience too.

Anybody over a certain age who hears the name Pete Best will be familiar with the saga of the so-called “fifth Beatle” and the life he lost out on. Rather aptly, we meet in Lost Lane, a music venue off Grafton Street, where he was due to play a gig on March 29th, now cancelled due to the Covid-19 crisis. But as soon as we start talking, it’s clear that despite the events of 1962 he doesn’t feel lost, and hasn’t for a very long time. He’s 78 now, and looks back with pride not just on his part in Beatle history, but his resilience too.

‘There came a period in my life when I was like, to hell with what happened yesterday’

At the height of Beatlemania, Best attempted suicide, but he has always denied it was because of depression related to being fired. “You should never ask someone who has tried to take their own life why they did it,” he said. “ I don’t know why I did it. All I know is my mother and my brother Rory found me. My mother gave me such a talking to and I vowed I would never do anything like that again. And I never will.”

How did he cope in a world that never lets anyone forget about The Beatles? “I think if I’d kept reflecting about what happened yesterday, all the time, and it was like a nightmare to me, I would have ended up bitter and twisted. But there came a period in my life when I was like, to hell with what happened yesterday it’s about today and tomorrow.”

In the end being an ex-Beatle, and carrying the weight of the criticism of his former bandmates, gave him purpose, a reason to prove himself. Over the years he had to endure public comments from various band members who critiqued his drumming and aspects of his personality in attempts to justify the sacking.

In the end being an ex-Beatle, and carrying the weight of the criticism of his former bandmates, gave him purpose, a reason to prove himself. Over the years he had to endure public comments from various band members who critiqued his drumming and aspects of his personality in attempts to justify the sacking.

“You’re the Beatle who got kicked out because you were crap. So there’s always been a point where I’ve had to prove myself. I haven’t talked about it, people make their own impressions about what a drummer is about. So I’ll perform on stage and the audience can make their own mind up. I’m glad to say that the consensus of opinion is yeah, you’re a great drummer, Pete. I’m happy with that.”

He might not be John, Paul, George or even Ringo, but he was still a Beatle, which means it’s still a thrill just to hear him talk about his days in the band, “propping up bars across Hamburg” with “gentle, tender John” – he was closest to Lennon – or having mock fights with the band on stage at The Indra club on The Reeperbahn. Or his enduring fondness for I Saw Her Standing There, one of the first Beatles originals he ever played on drums.

Ireland can lay claim to the former Beatle, which is also a bit fab. His grandfather Major Thomas Shaw, who was stationed in India at the time of the Raj, came from Dublin, while his biological father, a soldier who died when he was a baby, was also Irish.

His half-Irish mother Mona Best has her own place in Beatle history. After she was widowed, Mona married again and travelled to Liverpool, where she set up the Casbah club in the basement of their sprawling home, where The Beatles (as The Quarrymen and later The Silver Beetles) played their first gigs.

His half-Irish mother Mona Best has her own place in Beatle history. After she was widowed, Mona married again and travelled to Liverpool, where she set up the Casbah club in the basement of their sprawling home, where The Beatles (as The Quarrymen and later The Silver Beetles) played their first gigs.

Even after her son Pete was sacked from the band, Mona kept in touch with the Beatles. “She was very diplomatic,” says Best. When the cover art was being done for Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Lennon asked Mona if he could borrow her dad’s army medals, and he wore them on the cover of the album.

The medals are one of hundreds of exhibits in the Magical Beatles Museum on Mathew Street in Liverpool, run by Best’s younger brother Roag. (Roag is central to another bit of Beatles lore. His father is Neil Aspinall, the Beatles driver and later the managing director of Apple Corps. Aspinall had an affair with Mona when he was a lodger in the house and her husband was away.)

He had not seen or spoken to him in decades, but Best still cried when he heard of the murder of his old friend John Lennon in 1980. He has never spoken to any of the Beatles since he was forced out of the band. Reparation of sorts came in 1995 when Aspinall called (“Paul McCartney claims he called me but he didn’t,” says Best) to discuss The Beatles Anthology, which was to include some tracks featuring Best’s drumming, for which he would be paid royalties.

It’s another source of pride for Best that seven of the tracks on Anthology 1 feature his drumming: “Seven out of 60 tracks was quite a lot. And I’d like to think with that amount of tracks over a short period of time, it showed the important role I played. Whether that’s the case or not, I don’t know – you’d have to ask them.”

How much money did he get in royalties? “It wasn’t far short of a million,” he says. The money was welcome, even if, as he says, he was “well set” at that stage of his life, having made a good living from being Pete Best of the Beatles and Pete Best, musician in his own right.

He has his Beatles association to thank for another important part of his story – he’s been married to Kathy for 58 years, after first meeting her at a Beatles gig.

Lennon and Harrison are dead now, while Starr had nothing to do with the decision to replace the drummer. So there’s only one Beatle left who was directly involved in the banishing of Pete Best. Does Best forgive McCartney? “I’ve nothing to forgive him about … they made a decision as young men which was safeguarding their future. Okay, it could have been handled better. I was the fall guy for it, I suffered, but I’m not holding them to task over it. If I’d have been in the same situation and I was another member of the band, maybe I’d have been one of the bad guys.”

“I’ve no regrets,” he continues. “I think I’m a lucky guy. I’m very proud of what I’ve achieved as a person, of the examples I’ve set to people to get on with your life, to pick yourself up. I’ve been an inspiration. And I’m proud of that.”

irishtimes