On Feb. 4, 1970, John Lennon and Yoko Ono made a very different sort of donation.

The duo had recently made the acquaintance of London-based activist Michael X, who’d reached out to them after they made headlines for paying fines incurred by anti-apartheid activists who’d interrupted a rugby match between Scotland and South Africa. Inspired by the gesture, X asked John and Yoko to support the Black House, a home for disadvantaged youth in London, and they agreed.

But instead of offering money, the Lennons hatched a plan for the latest in a series of publicity stunts. Having recently cut off their hair (which they thought would have the added benefit of allowing them to travel more freely in public), they offered to exchange it for a pair of Muhammad Ali’s boxing shorts — an odd celebrity bartering program that was supposed to benefit a pair of projects, with the hair being auctioned off to support the Black House and the shorts being sold to raise money for John and Yoko’s peace campaign.

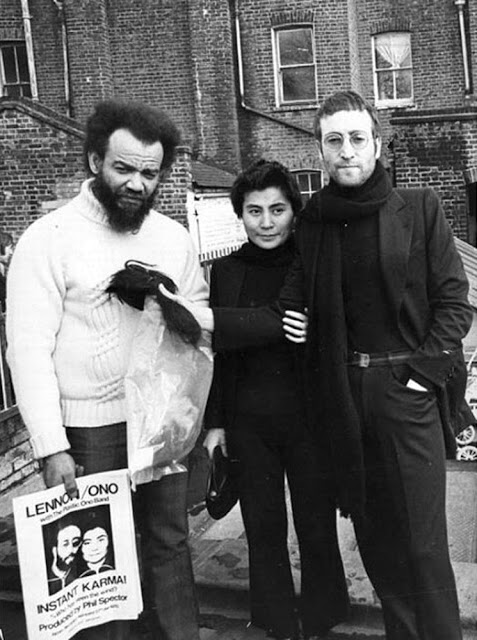

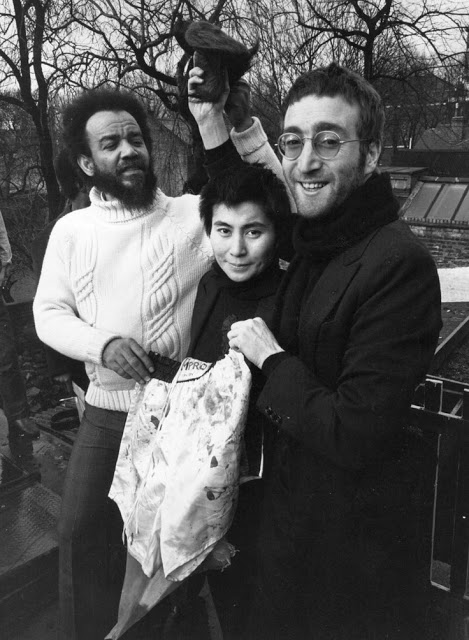

The haircut took place in Denmark on Jan. 20, 1970, and John and Yoko met up with X on the Black Center’s rooftop on Feb. 4, where they held a press conference to announce their plans and posed for photos with the hair. Lennon proved typically flippant at the gathering, shrugging that he’d decided on a new look because he was “cheesed off” at his hair (“it was gettin’ in me ears”) and saying he didn’t care whether people saw it as nothing more than a stunt.

Michael X, meanwhile, operated under a cloud of suspicion for much of the rest of his life, arrested for extortion following the Black House’s destruction (John paid his bail) and ultimately fleeing to his native Trinidad, where he started a commune that also burned in 1972. Investigators discovered corpses buried in shallow graves on the site, and he was hanged in 1975.

“I’ve always been politically minded, you know, and against the status quo,” John said in a 1971 interview. “It’s pretty basic when you’re brought up, like I was, to hate and fear the police as a natural enemy and to despise the army as something that takes everybody away and leaves them dead somewhere. It’s just a basic working-class thing, though it begins to wear off when you get older, get a family and get swallowed up in the system. In my case, I’ve never not been political, though religion tended to overshadow it in my acid days. … And that religion was directly the result of all that superstar s— — religion was an outlet for my repression. I thought, ‘Well, there’s something else to life, isn’t there? This isn’t it, surely?’”