This fall Disney+ unveils the three-part documentary, which mines long-lost footage for a portrait of the band’s final chapter that’s so unexpected it surprised even Paul McCartney.

It’s the Beatles as none would ever see or hear them again—their last live performance as a group, January 30, 1969. The approximately 43-minute sequence from director Peter Jackson’s forthcoming documentary, The Beatles: Get Back—screened exclusively for Vanity Fair—shows the full, uninterrupted concert on the roof of 3 Savile Row, the band’s headquarters, including iconic performances that would appear on their last album, Let It Be. The original footage, taken from at least nine different cameras, has been scrubbed to astonishing clarity, detail, and color, a rapturous window in time. The six-hour doc will run on Disney+ over three nights on November 25, 26, and 27.

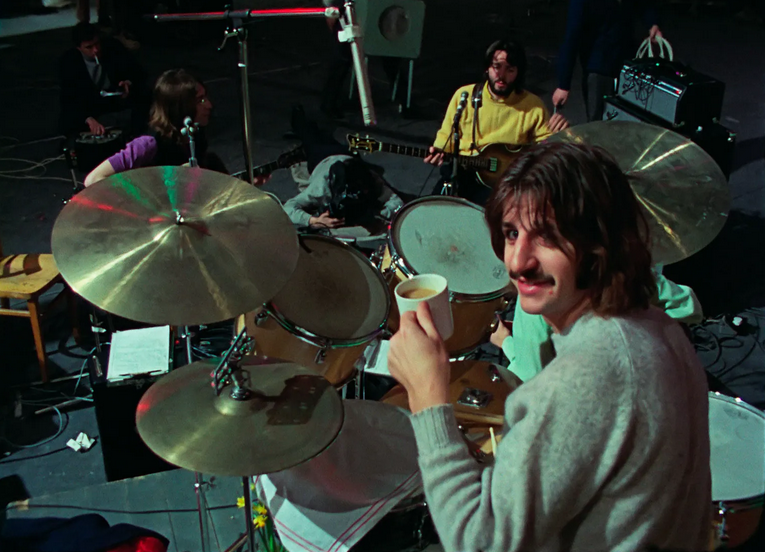

“We went to London and screened that to Apple,” says Jackson, referring to the company founded by the Beatles in 1968, which still manages their legacy. “And they were excited. Then Paul saw it, and Ringo saw it. And then the whole emphasis at that point became, ‘Let’s have the entire concert in the film. Let’s just show the whole thing.’ ”

The whole thing—including a comic subplot involving a baffled 19-year-old policeman responding to noise complaints and getting a sly runaround from Apple staffers—forms the climax of Jackson’s documentary, a 21-day diary of the Beatles in their intimate creative world. Drawn from nearly 60 hours of archival footage, it depicts the band jamming, writing, arranging, clowning, sparring, riffing, struggling, and finally succeeding to make Let It Be.

All this footage was originally shot for Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s vérité film Let It Be, which included a roughly 22-minute version of the rooftop concert but became known, by the few who saw it, for very different reasons. The movie premiered in May 1970, a month after the Beatles broke up, and was largely regarded as depressing evidence of the band’s dissolution—before promptly going out of circulation. In black-market versions, the original 16-millimeter film, converted to 35-millimeter for the big screen, looked somber, saturated in blues and greens. A Beatles fanatic since the 1970s—he was eight when they broke up—Jackson himself owned a fourth-generation bootleg on VHS, the muddy quality confirming his grim view of the period. Indeed, the director was the first skeptic of Apple’s project to disinter the footage. “I actually didn’t say yes,” recalls the three-time Oscar-winning director of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. “I said, ‘Can I look at all the footage first? And then I’ll let you know.’ Because I was thinking, I’d love to make a Beatles film, but I don’t want to make the Beatles-breakup film. That’s the one Beatles movie I would never want to make.”

And so after first meeting with Apple, Jackson returned to his home in New Zealand with the unedited footage from the movie (the “rushes,” in filmmaking argot), and sat down to see for himself. “I was waiting for it to go bad,” he says, “and I had a kind of heavy heart.”

As he watched, says Jackson, history shifted: “What I found is that I was laughing continuously. I just was laughing. I was laughing and laughing and laughing, and I didn’t stop.”

When Jackson went backstage at a Paul McCartney concert in Auckland, New Zealand, in 2017, he was surprised to find McCartney nervous to meet him, concerned with what Jackson had found in the footage. “I could see on his face he was imagining the worst,” says the director. “I just said to him, ‘Look, I’ve got to say, it surprised the hell out of me because I was expecting it to be a miserable experience for you. I expected to have to witness a rather bleak moment—but it’s actually the exact opposite. It’s incredibly funny. It’s incredibly lively. It shows you guys having a great time.’

“And he couldn’t believe it,” says Jackson. “He said, ‘What? What? Really? Really?’ And it certainly surprised him. Because he has never seen this stuff, even though he lived through it. It’s a long time ago, and subsequent events, I think, just muddied the whole memory of this thing.”

Last year, when Disney released a teaser for Get Back—meant to assuage expectant fans after the project was delayed for a year because of COVID-19—the montage of never-seen footage showing Lennon gleefully horsing around the studio with McCartney (doing a comic version of “Two of Us” through clenched teeth), and Ono chatting warmly with McCartney’s wife, Linda Eastman, looked revelatory, astonishing, and a bit suspicious to fans with even a passing knowledge of Beatles history. Was Jackson cherry-picking moments of levity to sell a revisionist history? A whitewash? “I don’t think they’ll feel that when they’ve seen it,” Jackson says, “but I understand where that’s coming from. This is not what you read in the books.”

In the weeks after the recordings, John Lennon recruited manager Allen Klein to take over the band’s business affairs, and McCartney hired his own father-in-law, attorney Lee Eastman, to counter Klein’s machinations, leading to a vicious legal battle that lasted long after the band dissolved. In the aftermath, Lennon savaged the Let It Be sessions, telling Rolling Stone, “They were writing about [Yoko] looking miserable in the Let It Be film, but you sit through 60 sessions with the most bigheaded, uptight people on earth and see what it’s fuckin’ like, and be insulted just because you love someone.”

And so went the story until 48 years later, when Apple Corps CEO Jeff Jones and Apple executive Jonathan Clyde invited Jackson to their offices in London to discuss a traveling Beatles exhibition that would feature unrelated archival films. They asked Jackson whether he could update old footage using the same technology he used to revive vintage World War I reels for the acclaimed 2018 documentary They Shall Not Grow Old. When Jackson casually asked about the Let It Be movie, he was told that a separate project to make a new documentary from the rushes was in the works—but that the original director had just dropped out. At this, Jackson perked up. “So I just put up my hand and I said, ‘Well, if you’ve just lost a filmmaker, I’m sitting here, I’ll do it,’ ” he says.

The Beatles exhibition never happened, but after Jackson reviewed the Let It Be footage—twice—he realized he would be telling a much different story from the one most people understood. Unlike Ron Howard’s Eight Days a Week: The Touring Years, the 2016 documentary about the mid-’60s period before the Beatles, overwhelmed by fan mania, stopped playing live, Jackson’s film isn’t just a delicious peek at lost footage (though it is that). It’s an amendment to the received history.

Though Get Back is made for modern eyes decades after the events themselves, it’s faithful to the intent of the original, which was to chronicle the band’s return to live performance after they ceased playing concerts in 1966. Director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, the son of Irish actor Geraldine Fitzgerald, was the 28-year-old director of British pop music TV show Ready Steady Go! when the Beatles asked him to produce a series of promotional movies for their 1968 singles. For a “Hey Jude” film, Lindsay-Hogg brought in a small audience—a mix of young people and regular “folk,” like a village postman—to sing along to what would become a legendary chorus. The experience revived the Beatles’ desire to play in front of people, and McCartney hatched a plan to make a TV show with taped performances of new Beatles songs before a small audience. The show would include a montage of behind-the-scenes vérité footage of rehearsals. “Paul was the driving force behind the whole project,” says Lindsay-Hogg.

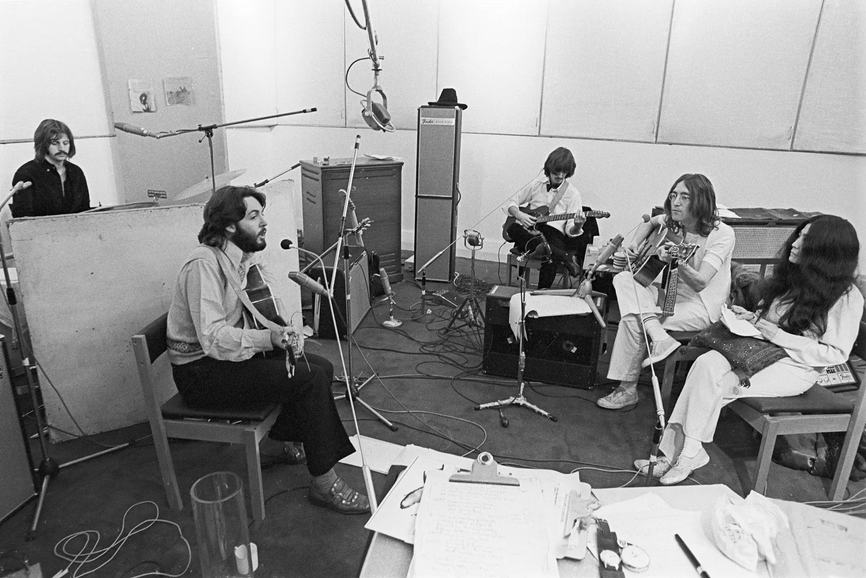

And so on the second day of January, 1969, the Beatles showed up at the cavernous Twickenham Studios in London to begin rehearsing songs for a TV show that would also be the basis of a live album. They chose Twickenham because Starr was shooting a movie there, The Magic Christian, costarring Peter Sellers.

At Twickenham, the Beatles rehearsed “Get Back,” “Two of Us,” and “The Long and Winding Road,” among others. And then, on day seven, Harrison walked out following arguments with McCartney. “George quits,” says Lindsay-Hogg. “Everything comes to a halt for a couple of days, and we’re all sitting around and doing nothing much. And everyone’s tetchy. Paul’s tetchy. And then George will [only] come back if we go to Apple—the studio which they have in the basement.

“That little episode,” he continues, “has been taken and completely blown up by some people to represent acrimony between George and Paul and underlying severe tension. And in fact, it’s just a small little cloud which passes over their working relationship in five minutes. That’s all it was.”

But the conflict was a major pivot in the production. The TV show idea was scrapped, and instead Beatles management decided to expand the project into a feature film to fulfill a three-picture contract that manager Brian Epstein had forged with United Artists before he died in 1967. (The first two films were A Hard Day’s Night and Help!) Bowing to Harrison’s demand, the Beatles moved the sessions to their recording studio at Apple, and Lindsay-Hogg and crew continued shooting for a documentary.

For his own project, Jackson decided that when Harrison and McCartney begin fighting—a brief but tense scene in which McCartney placates a wounded Harrison after criticizing his guitar parts—he would show not only that but the aftermath as well. Consequently, Jackson says, Get Back will be more revealing than the original, not less. “It’s a lot tougher movie than Let It Be,” he says. “I mean, Let It Be couldn’t show George leaving the group, which he did on the seventh day, and then he obviously came back again. Let It Be never showed that.”

Jackson says he didn’t need to manipulate Lindsay-Hogg’s original footage—or include talking heads to contextualize things—to create a dramatic plot. The sessions formed their own story, and Get Back, he decided, could simply be a “documentary about the documentary.”

“If this was a fictional movie about a fictional band, having one of the band members walk out at the end of the first act—it’d be the ideal thing that you’d actually write into a script,” says Jackson. “So, weirdly enough, these guys are playing out their real life. They were not playing it out [as] a movie or a script—that was the truth of their life. And yet, somehow, in terms of these 21 days, it kind of weirdly fits it. And then the triumphant third act where, against all odds, they’re up on the roof, playing—fantastic.”

Lindsay-Hogg needed a live performance for the climax of his documentary, so he and the Beatles bandied about possibilities. One involved an amphitheater on the coast of Africa at sunrise, with people streaming in like nomads arriving to the Holy Land; another, encouraged by Lennon, imagined a concert on the deck of an ocean liner full of fans at sea. Ultimately, given the logistics—and Harrison’s reluctance to play live again—Lindsay-Hogg proposed they go up to the roof of Apple Records and play an impromptu lunchtime concert. The band tentatively agreed, and support beams were built under the roof to hold the weight of the gear. But even in the moments before it was to happen, the band nearly didn’t do it. As Lindsay-Hogg describes in his memoir, Luck and Circumstance, the Beatles idled in the stairwell as McCartney tried rousing his bandmates:

The six of us stood there, stasis about to set in, momentum about to be fatally lost, ennui about to settle its cloud on our beings.

But one voice had not been heard from. Eyes under lids looked to that person. Time froze.

“F**k it,” said John. “Let’s do it.”

By the time Lindsay-Hogg screened the first cut of the Let It Be movie for the band—the night Neil Armstrong walked on the moon—there were clear signs that the Beatles were fracturing. The day after the screening, an Apple executive called Lindsay-Hogg to say there was perhaps too much Lennon and Ono footage in the movie. “He said, ‘Well, let me put it this way, I’ve had three phone calls this morning,’ ” says Lindsay-Hogg. “So I get the message that some of John and Yoko should come out.”

He recut the film and it premiered in May 1970, by which time the Beatles had officially broken up. None of the band members showed up for the film’s premiere in London, and history’s judgment began to harden around Let It Be as a breakup documentary. When Lennon and Ono watched the final cut—with Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner and his wife, Jane, in a movie house in San Francisco—they both wept while watching the rooftop sequence.

In the decades since, the Let It Be film was essentially buried. After their breakup and the years-long financial and legal battles, the Beatles rarely agreed on much, but they did seem to agree that the Let It Be film was too bleak—and emotionally painful—to revisit.

A significant technical issue also hampered any revival: In 1971, says Jackson, an Apple employee who worked in the Savile Row studio stole 140 hours of the audio, which left only a mono version used for the final cut of the film. The stolen tapes contained hours of sound recorded when the cameras weren’t rolling, meaning there was potentially even more revelatory evidence to be unearthed. “They eventually got Interpol involved,” says Jackson. “In the late ’90s or early 2000s, they did a sting operation in Amsterdam and recovered all of the tapes, apart from 40. There was about 560 quarter-inch tapes. There are still 40 missing, but we managed to find some of that sound through other sources.”

As Apple has released more archival material in recent years, the historical perspective of the Let It Be era has shifted. Mark Lewisohn, the foremost Beatles scholar in the world, spent a month listening to the nearly 98 hours of studio recordings the Beatles made in January 1969 and, like Jackson, was amazed by what he discovered, declaring, “It completely transformed my view on what that month had been.” Far from a period of disintegration, says Jackson, “these three weeks are about the most productive and constructive period in the Beatles’ entire career.” The tracks you hear on Let It Be were recorded during this three-week period. The band also rehearsed three-quarters of the Abbey Road album, about half of Harrison’s All Things Must Pass album, a half dozen songs that would later appear on McCartney’s solo albums, and a couple that would show up on Lennon’s. It was, Jackson marvels, “the Beatles doing these.”

Last year, McCartney told the Sunday Times that seeing uncut footage from Get Back was a relief precisely because it countered his lingering guilt over the breakup of the Beatles: “It was so reaffirming to me. Because it proves that my main memory of the Beatles was the joy and the skill…. I bought into the dark side of the Beatles breaking up and thought, ‘Oh god, I’m to blame.’ I knew I wasn’t, but it’s easy when the climate is that way to start thinking so. But at the back of my mind, it was always this idea that it wasn’t like that, but I didn’t see proof.”

After talking to McCartney in New Zealand, Jackson went to Starr’s home in Los Angeles to show him the footage on an iPad (“He was laughing, I was laughing”), and began corresponding with Olivia Harrison, George’s widow, who threw her support behind the project despite the documentation of George’s discontent. “She saw the rooftop concert about the same time as Paul did,” says Jackson. “She’s seen it about seven or eight times since. She’s very supportive.”

But what of Ono? For decades, she was a vigilant and astute gatekeeper of Lennon’s legacy, a powerful and opinionated voice among the four parties who control how Beatles music and history is curated and reissued. McCartney, in interviews, has tried to correct Ono’s story line that her late husband was the most important Beatle, the true genius of the band. As he told me in 2015, “Once John got murdered, he became the martyr, the Buddy Holly, the James Dean character. Because of the atrocity it was. A revisionism started to go on, and Yoko certainly helped it.”

There’s no denying that the first cracks in the Beatles façade had already appeared by the time of the Let It Be sessions, and that both fans and the press saw Ono as the bête noire in the plotline. For Get Back, Jackson says Lennon’s son Sean represented the Lennon estate and watched the rooftop sequence in London last year. Ono’s current status is unclear, but Jackson says he isn’t beholden to anyone’s agenda and has had control over the final cut of the documentary. “I have [gotten] no edicts,” he says. “I mean, nobody from Apple, none of the Beatles, have told me what to do, or none of them have said to me, ‘Don’t show this, don’t show that.’ I’ve been given no censorship instructions at all. I’ve been left completely alone.”

Jackson is cognizant of the delicacy of a project in which he second-guesses another filmmaker’s creative decisions. He met with Lindsay-Hogg in Los Angeles in 2020 to show how his technology could transform the footage. “He showed me a comparison of my Let It Be’s footage and his stuff,” says Lindsay-Hogg, including how McCartney’s hair appeared as a single block of color in the original and “now you can see every single strand of hair.”

Lindsay-Hogg defends his own film as more “original” and “up” than people remember. He also says that Apple asked for his goodwill toward Jackson’s film, which he looks forward to seeing, and that he feels it’s Apple’s intention to possibly re-release Let It Be a few months after Jackson’s Get Back comes out. (Quentin Tarantino’s movie theater in Los Angeles, the New Beverly Cinema, has expressed an interest in screening Let It Be, if it is re-released, he says.)

As for Jackson, he’s developed a deeper admiration for the original, in part because of the circumstances under which Lindsay-Hogg labored, what with an increasingly acrimonious band hovering around him. “The Beatles that I’m dealing with now are Beatles that can’t remember January ’69,” Jackson says. “I mean, they literally can’t. Not really. And I don’t blame them.”

In a decisive and crucial creative act, Jackson says he avoided repeating footage from the original film. Even familiar scenes would use alternative camera angles. “One of our mantras is that Let It Be is one movie, and our movie is a different movie,” he says, “and we’re trying not to repeat any footage, with one or two tiny exceptions where we can’t do anything else. But we’re trying to not step on Let It Be’s toes so that it is still a film that has a reason to exist, and our movie will be a supplement to it.”

Fifty-one years after the group broke up, Jackson’s film is probably the last revelatory document we’re likely to see. That it also documents their last official album gives it a bittersweet power. Fans and scholars will likely debate whether Get Back is a revision of history or a correction. But it’s something everyone craves: more Beatles. Says Jackson: “Paul said to me at one stage, ‘Look, this stuff’s fantastic, because at the end of the day, I’m a Beatles fan.’”

vanityfair