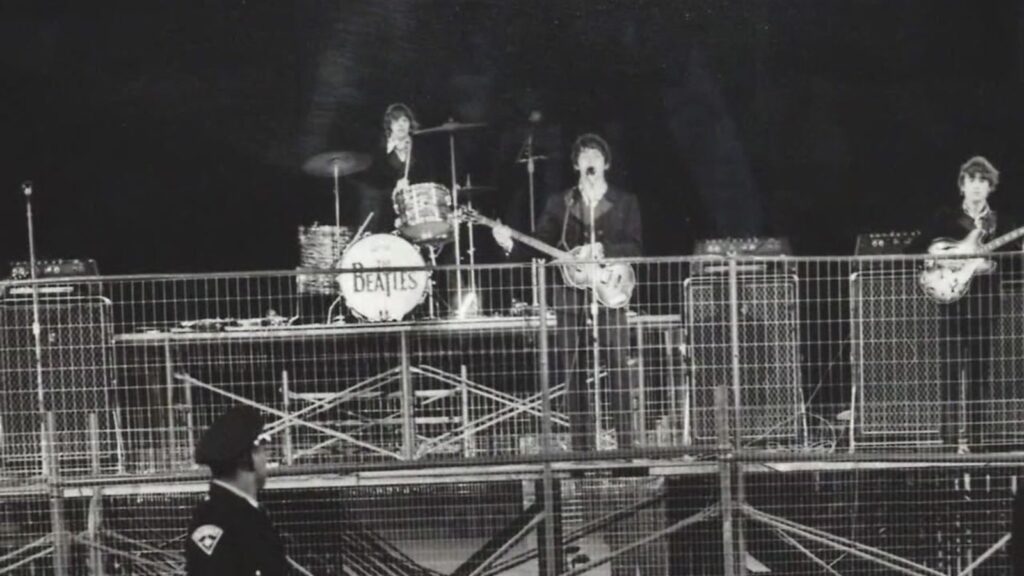

55 years ago, The Beatles played Candlestick Park.

1966 was a transitional year for the Beatles. Having grown weary of a never-ending whirlwind of hotels, press commitments and screaming crowds, the band reached a breaking point that eventually led them to make a radical decision that would forever change their career: They were going to stop performing live.

Adding to their exhaustion was a thirst for new musical horizons. The first few months of the year had been spent recording their new album “Revolver,” which came out in August to a collective realization that the band was innovating at a dizzying speed, but also that most of their new songs were impossible to replicate in concert. “Rather that permitting self-expression, live performances became a process of self-denial,” author Martin Cloonan explains in “The Beatles, Popular Music and Society.”

On Aug. 29, 1966, The Beatles arrived in San Francisco to wrap up their summer tour with a show at Candlestick Park. But what might at first have seemed like an unexceptional event actually signaled the end of an era, as they had all agreed this would be their final concert. “That’s it,” George Harrison famously sighed on the plane back to London. “I’m not a Beatle anymore.”

It had been a tumultuous tour, filled with “mishaps, rain-outs, and an undercurrent of fear,” as author Jonathan Gould describes it in his book “Can’t Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America.” First came tensions in Tokyo, where their Budokan shows fomented protests from the Japanese ultranationalist youth; then there was “the Philippines incident,” a diplomatic faux-pas triggered by the band’s refusal to abdicate a day off in order to attend an official lunch, which nearly cost them their freedom and even their lives (they were refused security on their way back to the airport, and the plane was denied permission to lift off at first). And by the time they landed in the U.S., John Lennon’s “more popular than Jesus” remarks had sent the fundamentalist South into an anti-Beatles crusade, with accusations of blasphemy quickly escalating to death threats.

But the madness wasn’t exclusive to the Bible Belt region. Outside Candlestick Park, a handful of young protesters from Sunnyvale gathered holding signs that read “Beatles today, what tomorrow?” and “Jesus loves you — do the Beatles?” confirming the band’s popularity wasn’t nearly as universal as it once had been — even in the progressive Bay Area.

In fact, if compared with the overwhelming Shea Stadium success a mere year prior, where more than 55,000 people saw the Beatles perform a sold-out show through a less-than-decent sound system, at Candlestick Park only 25,000 tickets, priced from $4.50 to $6.50, were sold, leaving 7,000 seats empty. Moreover, the contract required 15% of ticket sales to go to the city of San Francisco, resulting in actual financial loss for local promoter Tempo Productions. This was the third time the Beatles played San Francisco, but their first one at Candlestick Park; they had given two shows at the Cow Palace during their 1964 and 1965 tours, respectively.

On their way to the show, Paul McCartney asked the band’s press officer Tony Barrow if he had his tape recorder with him: “I said, ‘Sure, of course.’ [Paul] said, ‘Tape tonight, will ya? Record tonight.'” Although manager Brian Epstein had strictly forbidden any recordings, Barrow knew this was a special occasion: “It was fairly common knowledge among The Beatles, and not beyond The Beatles, that this was to be the last concert tour,” he later wrote in his book “John, Paul, George, Ringo & Me.” “Therefore tonight was to be the last concert they would ever give.”

After performances from supporting acts The Remains, Bobby Hebb, The Cyrkle and The Ronettes, The Beatles kicked off their 30-minute set (a standard slot at the time) with “Rock And Roll Music,” following up with a series of more or less classic numbers that included “I Feel Fine,” “I Wanna Be Your Man” and “Day Tripper.”

Near the end of the show, Ringo joined the other three downstage for a final photograph before returning to his drum kit for the last song. The band then closed their set with a version of “Long Tall Sally,” during which Barrow’s tape symbolically ran out.

Calling it “probably the most unique Beatle recording in existence,” Barrow later made one single copy for himself, giving the original to Paul McCartney — so it was with surprise he later found out a bootleg was circulating online: “It must have come either from Paul’s copy or mine, but we never did identify the music thief!”

Although the September edition of fanzine Beatles Monthly still alleged that a U.K. tour was in the works, Brian Epstein never succeeded in changing their minds. Panicking at the possibility of being made redundant since his contract with the Beatles was nearing expiration (even if they’d later affirm renewal was never in question), he dove deep into depression, dying a year later almost to the day. Ironically, Epstein missed the Beatles’ last concert because of a personal situation that had forced him to stay in Beverly Hills. “He never forgave himself for not being at Candlestick Park,” Beatles biographer Philip Norman revealed.

Candlestick Park represented a turning point for The Beatles on many levels, the most important probably being the beginning of their separation. “Playing in front of a live crowd, despite its hazards, kept the group’s identity intact,” Kevin Courrier explains in his book “Artificial Paradise.” “As long as they stayed on the road, the inner tensions of each group member was sublimated into the greater good of the band and its audience.”

But it also meant that in that late August in San Francisco, a new incarnation of the four-headed monster was born, a powerful colossus whose unavailability outside the studio only fed into the ever-growing pop mythology, further underlining its main agents’ new deified status. “[The Beatles’] opting-out of touring was in itself an affirmation of their determination to prove their self-sufficiency as artists,” critic George Melly wrote in 1971.

And if further proof was required, the release of their studio masterpiece “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” a year later in June 1967 dissipated any possible doubts anybody might have that the band was focused on making music without live performance in mind.

Although the San Francisco show was their final official concert, there was one more encore: an unofficial and improvised performance on Apple Corps’ rooftop in January 1969. By then, the dynamics between the band and their audience had irrevocably shifted: “You had a sense of a rare and odd occasion,” “Let It Be” director Michael Lindsay-Hogg explains in Peter Doggett’s “You Never Give Me Your Money.” “You were at a Beatles concert with nobody up there except yourself. And probably because they didn’t have the burden of an audience, they really did play for each other.”

sfgate