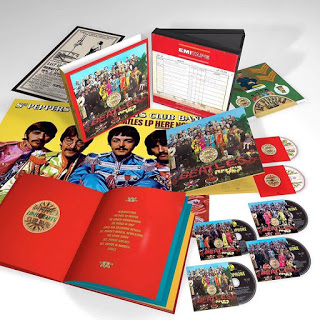

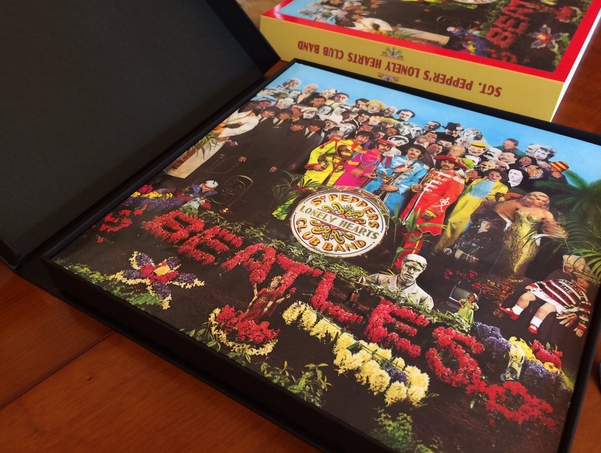

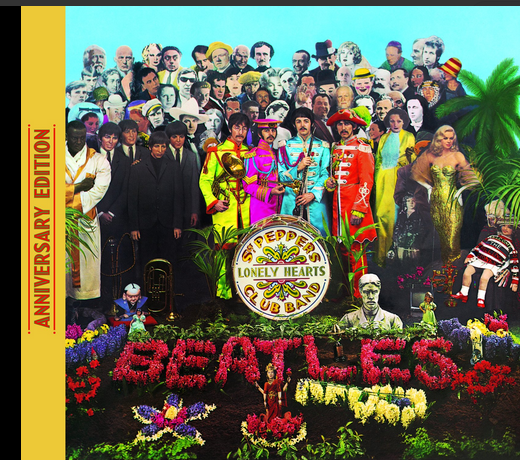

The Beatles‘ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which Rolling Stone named as the best album of all time, turns 50 on June 1st. In honor of the anniversary, and coinciding with a new deluxe reissue of Sgt. Pepper, we present a series of in-depth pieces – one for each of the album’s tracks, excluding the brief “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” reprise on Side Two – that explore the background of this revolutionary and beloved record. Today’s installment tells the story of the Victorian circus poster immortalized in “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!”

For a man who would famously imagine no possessions, John Lennon

had amassed an impressive volume of unusual objects by 1967. Kenwood,

his mock-Tudor estate in the London suburb of Weybridge, was packed with

what friend and Beatles associate Tony Bramwell describes as

“bric-a-brac.” Or, put another way, “a load of junk! Oddities and things

he’d pick up in a junk shop,” he tells Rolling Stone. “You’d pick it up and wonder what it was – he’d just buy it, take it home and stick it on the shelf.”

Guests arriving at chez Lennon were greeted in the entrance hall by a suit of armor christened “Sidney,” a World War I recruitment poster proclaiming “Your Country Needs YOU” and, occasionally, a lifelike gorilla costume. Elsewhere were vintage enamel advertising signs, an ornate Victorian wheelchair and an altar-sized Roman Catholic crucifix with an enormous Bible to match. “Cartoons, film posters, knitted dolls,” Bramwell adds to the list. “Things that Beatles fans had sent him and he’d say, ‘Oh, I’ll keep that one.’ Stuff like that. Lots of books, odd instruments that he never learned how to play – cellos and tubas and brass horns – and strange electronic things.” In his 2006 memoir, Magical Mystery Tours: My Life with the Beatles, Bramwell also describes a number of empty boxes, produced by the band’s electronics guru “Magic Alex” Madas, purported to contain a light ray that warded off negative energy. These were about as useful as the legendary “Nothing Boxes,” metallic cubes with eight lights that flashed in random order until the battery died. There were also more functional items, like a slot machine, pinball table, 40-disc KB Discomatic jukebox and an entire room filled with Scalextric toy racing cars (“That’s a hobby I had for about a week,” Lennon told profiler Maureen Cleave).

Lennon made a significant addition to his collection on January 31st, 1967, when the Beatles were filming the promotional video for “Strawberry Fields Forever” at Knole Park in Sevenoaks, Kent. Bramwell, on hand to produce the segment, accompanied Lennon when the shoot broke for lunch. “John wanted to go for a drink, so we walked onto the High Street and about three doors along from our hotel was an antique shop,” he recalls. “He went and fussed around in there and saw a poster stuck on the wall.” It was a framed Victorian circus advertisement, breathlessly hawking the “Grandest Night of the Season” – February 14th, 1843, a Tuesday – more than a century after the applause had died away. “Pablo Fanque’s Circus Royal, Town Meadows, Rochdale, and Positively the Last Night but Three!” the verbose headline trumpeted. “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite, (Late of Wells’s Circus) and Mr. J. Henderson, the Celebrated Somerset Thrower! Wire Dancer, Vaulter, Rider, Etc.”

The poster was dripping with arcane language and comical illustrations, and Lennon had to have it. “He thought it was amusing because of the drawing of the acrobat on it,” says Bramwell. “And he bought it for 10 shillings – about half a dollar.” Once back at Kenwood, it took pride of place in his den, not far from his piano, where it drew smiles from visitors. “It was just a funny poster,” Bramwell remembers. “It read old English. You’d wonder what some of the acts were supposed to be doing!” Indeed, the colorful language is not easy to decipher. The “somersets” undertaken by Mr. J. Henderson (on “solid ground,” no less) refer to somersaults, while the “garters” he was due to leap over were large banners held aloft by two pairs of hands. The “hogshead of real fire” was a colloquial term for a barrel set alight.

Though Lennon likely wasn’t aware of it, the billing featured some of the biggest stars of the Victorian age. Pablo Fanque, born William Darby, earned fame as a talented performer and the first black circus impresario in England, helming one of the country’s most popular shows for three decades. The headlining Mr. Kite was in fact William Kite, depicted on the poster playing a bugle while balancing his head on top of a pole, and Henderson – famous as a gifted tightrope walker, clown and acrobat – often performed an act with his wife, Agnes. It’s pure coincidence that these bygone celebrities, all long forgotten by 1967, wound up on the wall of a modern luminary.

As the Beatles dove headlong into sessions for what would become Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that February, Lennon found himself short on new material. A glance at the poster provided a welcomed dose of inspiration. “I had all the words staring me in the face one day when I was looking for a song,” he told biographer Hunter Davies. Keeping the archaic syntax intact, he borrowed a title: “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!”

Having found a starting point, the rest came quickly. “Everything in the song is from that poster, except the horse wasn’t called Henry,” he explained to Playboy in 1980. There were a few other minor alterations – the scene was moved from Rochdale to Bishopsgate, and Henderson was actually “late of Wells’s Circus” – but the majority was taken down nearly verbatim, with a degree of haste. “I wrote that as a pure poetic job. I had to write it because it was time to write and I had to write it quick because otherwise I wouldn’t have been on the album,” he admitted to Rolling Stone in 1970. For George Harrison, the process was a testament to his bandmate’s attentive eye for creative possibility. “That’s how you do it. You hear people say stuff, you hear a phrase that sounds good and you write it down and remember it,” he said in a 1992 episode of The South Bank Show. “I think he was just advanced for those days in his awareness that everything could be put into a song.”

Paul McCartney, based in London, made the drive out to Kenwood and together they assembled the lyrics. “We sat in his room and said, ‘OK, what are we going to write?’ And we noticed he had this old circus poster,” McCartney tells Rolling Stone. “So we said, ‘OK!’ We pulled most of the words directly off the poster, and then filled it in together. It had Pablo Fanque’s Fair, the Hendersons and Mr. Kite, a hog’s head of real fire – all those phrases were directly lifted off the poster.”

The serendipitous composition fell perfectly in line with the antique-chic aesthetic that imbued some of the band’s most recent recordings, particularly McCartney’s “When I’m Sixty-Four” and “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” The latter was tinged with the vintage militaria becoming fashionable with London’s hipster elite. “Around that time there were places like I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet and that brought back into vogue a lot of those old Victorian things and the nice way of putting things – ‘this night’s production will be one of the most splendid ever!’ That attracted us,” McCartney later explained to biographer Barry Miles in Many Years from Now.

Bolstered by the evocative arrangement courtesy of producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” is an enthralling finale to Sgt. Pepper‘s first side. But Lennon, his own harshest critic, voiced his dissatisfaction with the song soon after its release in an interview with Hunter Davies. “I hardly made up a word, just connecting the lists together. Word for word, really. I wasn’t very proud of that. There was no real work. I was just going through the motions because we needed a new song for Sgt. Pepper at that moment.”

Lennon often cited his most personal songs as his favorite works. It’s possible that “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” veered too far into fiction territory for his liking. “I’m not interested in third party songs,” he told Playboy just before his death, “I like to write about me because I know me.” But in the same interview, he admitted that his opinion of the track had improved. “The song is pure, like a painting, a pure watercolor.”