The Beatles’ illustrious eighth album, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” lends itself to anniversary celebrations. The central conceit of the album is that of a twentieth-anniversary concert by a once famous musical group that has returned from the oblivion of pop history to “raise a smile” on the faces of its aging, nostalgic fans. At the time John Lennon and Paul McCartney wrote that opening number, twenty years must have seemed like an eternity to them: more than enough time for a pop sensation like the Beatles, say, to fade from living memory.

As the recent media blitz of tributes surrounding the fiftieth anniversary of “Sgt. Pepper” illustrates, the Beatles and their alter egos in the Pepper Band are still very much with us––not least because “Sgt. Pepper,” more than any other single work, was responsible for generating the aura of artistic legitimacy that would institutionalize the presence of rock music in the mainstream of modern culture. The album inspired an unprecedented outpouring of reviews, cover stories, and sober cultural commentaries in newspapers, mass-circulation magazines, and highbrow literary journals, many of which had never covered rock as an artistic phenomenon before. “The Beatles are good even though everyone already knows that they’re good,” the composer Ned Rorem declared in The New York Review of Books, at the end of 1967, slyly acknowledging the way the group had transcended the limits of both condescension and connoisseurship. Rorem had already told Time magazine that “She’s Leaving Home,” the mock-Victorian parlor ballad on the first side of “Sgt. Pepper,” was “equal to any song that Schubert ever wrote.” Portentously titled “The Messengers,” Time’s cover story went on to enlist a chorus of well-known conductors and composers, such as Leonard Bernstein and Luciano Berio, in singing the praises of the Beatles’ music. The New Yorker greeted “Sgt. Pepper” with a “Talk of the Town” piece written by its editor, William Shawn, who posed as a “professorial-looking” Times Square record-store patron named “Lawrence LeFevre,” to extoll the album as “a musical event comparable to a notable new opera or symphonic work.”

Predictab ly, the acclaim that was heaped on “Sgt. Pepper” in the summer and fall of 1967 inspired a critical backlash. Richard Goldstein’s tone-deaf dismissal of the record as “an album of special effects, dazzling but ultimately fraudulent,” in the Times, inspired a firestorm of angry letters to the editor, which the paper published for weeks on end. But the most prescient criticism came from the British critic Nik Cohn, who agreed that “Sgt. Pepper” “was genuinely a breakthrough,” but complained that “it wasn’t much like pop. It wasn’t fast, flash, sexual, loud, vulgar, monstrous, or violent.” Cohn’s words presaged the rise of punk, which emerged, a decade later, as a corrective to the rock-as-art pretensions that “Sgt. Pepper” represented. “The Beatles make good music, they really do,” Cohn concluded, “but since when was pop anything to do with good music?”

ly, the acclaim that was heaped on “Sgt. Pepper” in the summer and fall of 1967 inspired a critical backlash. Richard Goldstein’s tone-deaf dismissal of the record as “an album of special effects, dazzling but ultimately fraudulent,” in the Times, inspired a firestorm of angry letters to the editor, which the paper published for weeks on end. But the most prescient criticism came from the British critic Nik Cohn, who agreed that “Sgt. Pepper” “was genuinely a breakthrough,” but complained that “it wasn’t much like pop. It wasn’t fast, flash, sexual, loud, vulgar, monstrous, or violent.” Cohn’s words presaged the rise of punk, which emerged, a decade later, as a corrective to the rock-as-art pretensions that “Sgt. Pepper” represented. “The Beatles make good music, they really do,” Cohn concluded, “but since when was pop anything to do with good music?”

It is now possible to see “Sgt. Pepper” as the hallmark of an era, which reached from the mid-nineteen-sixties to the mid-nineteen-seventies, when pop had a lot to do with good music––when some of the most profound and provocative music being made was also some of the most popular and commercially successful. This ten-year apotheosis of rock and soul was the result of a unique convergence of culture, commerce, and technology, in which the interplay of African-American and Anglo-American talent that had shaped the sound of popular music in the U.S. and Britain since the mid-nineteenth century was supercharged by the advent of multitrack recording, which turned studios into compositional laboratories and allowed musical artists to exert an auteur-like sovereignty over their work. At the same time, the advent of stereo records and FM broadcasting gave these artists the medium they needed by turning long-playing albums, rather than three-minute singles, into the commercial basis of pop.

Though “Sgt. Pepper” was hailed as a marvel of technical innovation upon its release, multitrack recording was still in its infancy in 1967, and the album was made using a jerry-rigged system of patched-together tape decks that required each layer of instruments and voices to be premixed and rerecorded in order to make room for additional overdubs. In the process of these so-called “reduction mixes,” the presence and clarity of the basic tracks were significantly compromised. Stereo records were still an anomaly in Britain at the time—so much so that the Beatles themselves did not bother to participate in the stereo mixes of the album, which were done mainly for the American market. Minor improvements were made when “Sgt. Pepper” was remastered by the Beatles’ producer George Martin in the nineteen-eighties, for release as a CD. But, for the past half century, “the act you’ve known for all these years” has come to us in a rather crude stereo format that placed the voices and instruments on one side or the other with precious little in between.

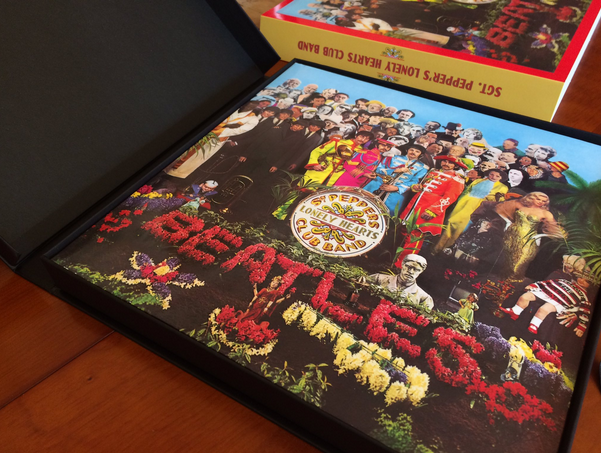

George Martin died in 2016, but his son Giles had worked with him for the last decade of his career, during which he assimilated a great deal of his father’s expertise, ingenuity, and impeccable musical taste. In preparing the silver-anniversary edition of “Sgt. Pepper,” Giles, with the full consent of the surviving Beatles, drew on the archives of EMI’s Abbey Road Studios to exhume the original, unreduced tapes, which were recorded during the marathon sessions that ran through the winter and spring of 1967. He digitized these tracks, fed them through a modern mixing board, and then, using the Beatles-approved mono mix as a guide, recast the album in true stereo. For Beatles enthusiasts who can’t get enough, the new reissue of “Sgt. Pepper” is also available in a deluxe package that includes a generous selection of outtakes, which provides a fascinating glimpse of the empirical process by which the Beatles went about their work.

George Martin died in 2016, but his son Giles had worked with him for the last decade of his career, during which he assimilated a great deal of his father’s expertise, ingenuity, and impeccable musical taste. In preparing the silver-anniversary edition of “Sgt. Pepper,” Giles, with the full consent of the surviving Beatles, drew on the archives of EMI’s Abbey Road Studios to exhume the original, unreduced tapes, which were recorded during the marathon sessions that ran through the winter and spring of 1967. He digitized these tracks, fed them through a modern mixing board, and then, using the Beatles-approved mono mix as a guide, recast the album in true stereo. For Beatles enthusiasts who can’t get enough, the new reissue of “Sgt. Pepper” is also available in a deluxe package that includes a generous selection of outtakes, which provides a fascinating glimpse of the empirical process by which the Beatles went about their work.

On the occasion of the album’s fiftieth anniversary, how does this refurbished version of “Sgt. Pepper” hold up? The famous cover photograph, staged by the Pop painter Peter Blake, now looks as dated as the Edwardian-era portraiture it was meant to satirize. Yet, for all its identification with Swinging London, the Haight-Ashbury, and the Summer of Love, the album effortlessly transcends the bounds of its historical moment. As Ned Rorem might have said, “Sgt. Pepper” is a masterpiece even though everyone already knows that it’s a masterpiece. The giddy, glad-handing promise of pop (“We’d love to take you home with us!”) still exerts its seductive power over the popular imagination. And the world is still full of girls like the ethereal “Lucy in the Sky” and the earthy “Lovely Rita,” desperate daredevils like Mr. Kite, and cheerfully reformed domestic tyrants like the one in “Getting Better.” The experience of immersing oneself, as a listener, in the rich stylistic swirl of satire, sentiment, and sensation of the Pepper Show, only to be torn from it, at the very end, by the sublime majesty of “A Day in the Life,” on which the Beatles abandon the gaudy self-assertion of their Pepper Band personae to expose the deep well of alienation and vulnerability that lies behind the mask of the crowd-pleasing entertainer––none of this has lost its power to astonish, enlighten, and delight.

source:newyorker