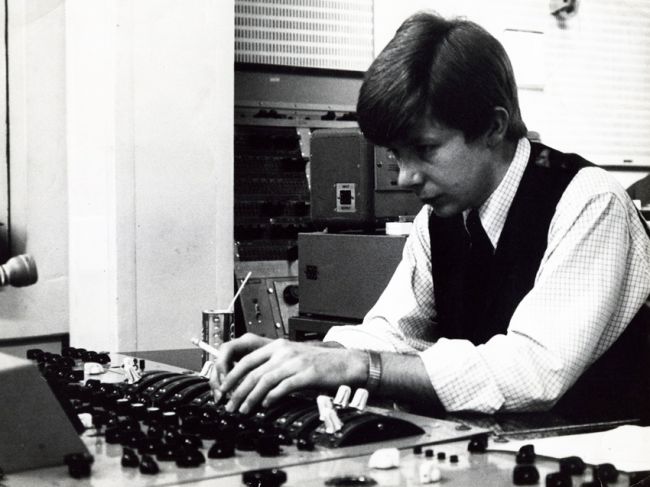

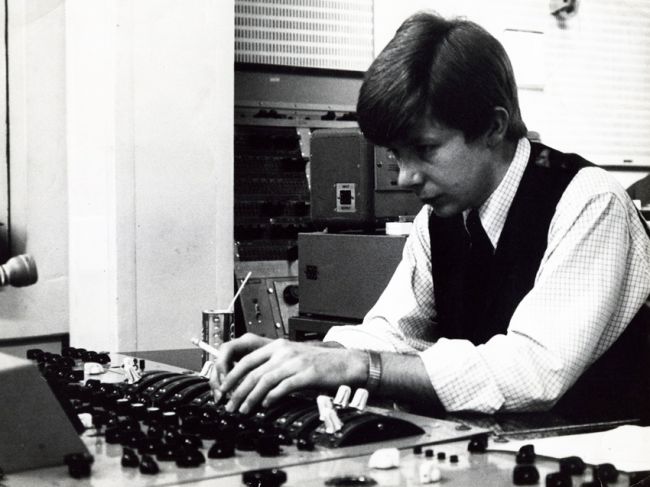

Ken Scott worked with the likes of The Beatles, David Bowie and Elton John. He talked to Duncan Seaman about his career. Even the briefest glance at Ken Scott’s CV suggests a musical life well lived. Key albums by David Bowie, Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd, George Harrison, Elton John, Supertramp, Billy Cobham and John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra all feature his production, engineering or mixing skills. But one of the most significant of all was his very first job, as a 16-year-old assistant engineer – or “button pusher” – at Abbey Road studios when The Beatles were making what was to become the second side of A Hard day’s Night.

Scott says interest in the backroom side of music had been sparked at the age of 12-and-a-half “when I was given a tape recorder for Christmas and that started the ball rolling, I loved recording, I loved tape”. The “embarrassing side of it” came when he was 14: “There was a TV series called Here Come The Girls and there was an English pop singer called Carol Deene that I was totally in lust with and she happened to be on and at one point during the show they showed her singing into a microphone and panned out to this big window and there was this grey thing there and someone sitting behind it and that’s when I knew: I want to be that person. “I eventually found out that was called a recording engineer and that’s what I started to work towards. It just so happened that the studio she was singing in was No 2 Studio at Abbey Road and the person behind the desk was an engineer called Malcolm Addey who became a mentor and a friend.” Addey was just one of several studio legends that Scott was to work with at Abbey Road. Others included Norman Smith, who would helm The Piper At The Gates of Dawn for Pink Floyd, and the inimitable George Martin.

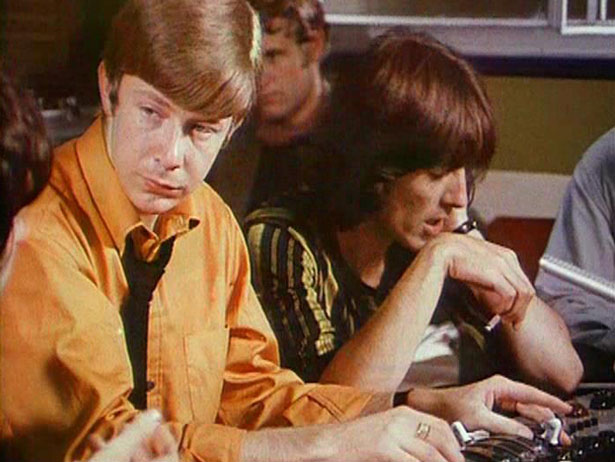

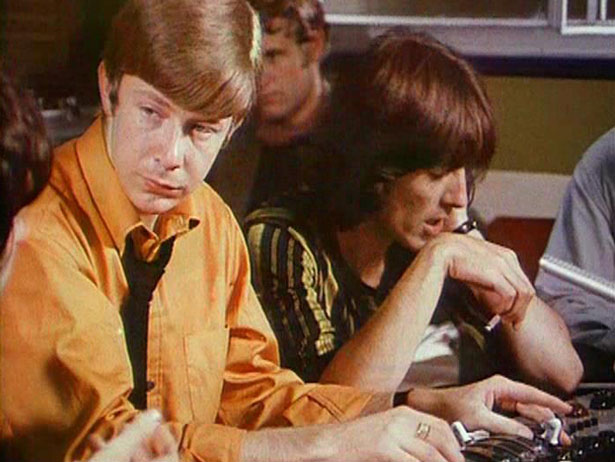

When Scott was first drafted in to work with John, Paul, George and Ringo in 1964, he says: “They were the biggest band in the world and I was a huge fan.” For a 16-year-old, the experience was “phenomenal – there was none of the thought of the history that was being made; it was just making great music”. Scott would go on to engineer The Beatles’ The Magical Mystery Tour, a string of landmark singles and The White Album. He says “of course” there was a joy in being able to witness the creative processes that the band were going through. Equally, he adds: “It was the most incredible learning experience. Being partnered with George Martin, it was not necessarily at the time realising how he worked and his methodology in the studio – that came later, looking back at how I worked in comparison to other producers that I’d learnt from – George being the number one teacher or mentor. Knew we were making great music and that’s what it was all about. “The courage that The Beatles had, which I saw again with Bowie, it was not bothering about what the public want, what they expect; it’s coming up with things different and the seriousness of being able to totally change what you’re recording. When The White Album first came out a lot of people hated it because they were looking for Sgt Pepper II, but The Beatles being the way they were they didn’t want to do the same thing again. So they decided to go back to their roots, more of the band that they were originally, rock ’n’ roll and a bit dirtier. Pepper was a very clean recording, everything was perfect; they didn’t want that for their next album.” Working with a young Pink Floyd was, by contrast” “not as interesting as you might expect”, Scott says. Though a lot has faded from memory, he recalls his last session with the band, then led by Syd Barrett was “gruelling but fascinating”, particularly as his friend Norman Smith was producer. “I didn’t notice in the studio how influential within the band Syd was; it seemed to be all mutual,” he adds. “I only actually remember one session with him as a solo artist and I remember it because he never turned up – well, he turned up but not when I was there. I’d closed the session down because no one had bothered to turn up and he appeared at the studio then.”

In 1969 Scott moved to Trident Studios in Soho. There he joined Gus Dudgeon, stepping in to mix Elton John’s album Madman Across The Water after fellow Trident engineer Robin Cable suffered serious injuries in a car accident, then going on to work on Honky Chateau and Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player. John by that stage was “already huge” and Scott had already seen “what he was capable of by the early albums”, yet the engineer quickly realised the singer was determined to “do something different and I came in on that changeover” from “big orchestral stuff” to being “a bit more rock ’n’ roll and record with his touring band, with the addition of a guitarist – Davey Johnstone”. Their working relationship ended after an aborted attempt to record Goodbye Yellow Brick Road in Jamaica, but by then Scott was busy co-producing several albums by David Bowie, including Hunky Dory, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stadust, Aladdin Sane and Pin Ups. Scott says their first conversations took place with Bowie’s wife Angie and his publisher Bob Grace as they listened to the singer’s latest demos. “We went through those and decided on a lot of the songs that we were going to do on Hunky Dory and then it was go in and do it. Neither David nor I had really produced before, so it was a learning experience for us. We just did what felt right as we did it and because it was sounding good our confidence grew and grew. Because we were growing together we didn’t need too much of a conversation as to what was going to happen; it just happened naturally. And it was the same with the musicians, with Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder on bass and Woody Woodmansey on drums – we all grew together and we were heading in the same direction so we didn’t need too many conversations as to what was needed.” Scott’s considerable renown for his work with Bowie and on Supertramp’s hit album Crime of the Century led to opportunities to work in the US. In 1976 he relocated to Los Angeles and would go on to work with The Tubes, Devo and Duran Duran. Over the next three decades he noticed studios and clubs starting to close and “LA became heavy metal hair-band orientated and it became dull and uninteresting” and so decided to return to Britain. He now lives near Harrogate and lectures in production at Leeds Beckett University, imparting some of his vast knowledge of the industry to students. In 2012 he wrote a memoir, Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust, and still loves recording studios, talking enthusiastically about mixing music for up and coming Leeds band Heir that are, he says, “incredible – we did it the old-fashioned way and it sounds amazing and they were so pleased to do it the way it used to be done. They’d got used to the more modern way of recording and found it unfulfilling. This worked perfectly and the three tracks we did are great.”

source:yorkshirepost