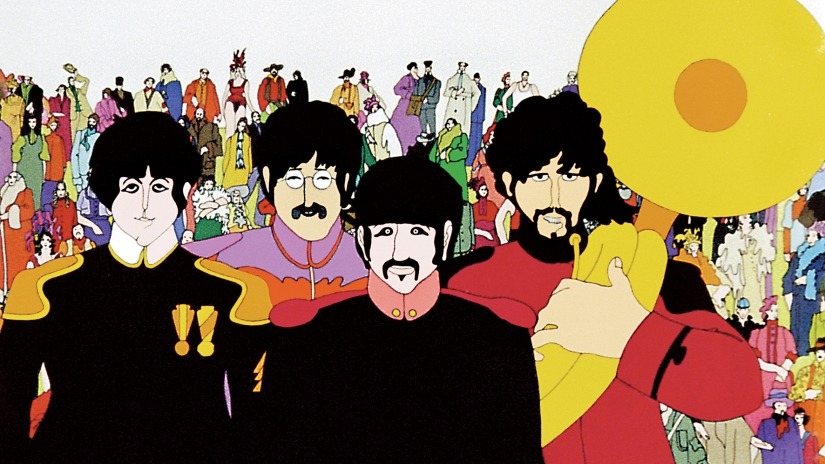

To commemorate its 50th anniversary, “Yellow Submarine” is being re-released, in a startling new 4K print (it was cleaned and restored by hand, one frame at a time), by Abramorama, the distribution company that had a success two years ago with Ron Howard’s deft and revealing early-Beatles-on-tour documentary “Eight Days a Week.” The “Yellow Submarine” revival kicked off on Monday, July 9, and the movie, which is playing in 79 theaters, will be expanding throughout the summer. It’s a delight to go back to, or to see for the first time, and what unites those two experiences is that even now, in the middle of the renaissance age of animation, “Yellow Submarine” stands apart, reminding you of what a cartoon feature can truly be: a miraculous mutating object that keeps flipping reality inside out.

In 1968, the movie definitely felt “different,” but that was only to be expected. “Yellow Submarine” was a fairy-tale extension of the Beatles’ brand, and one had come to count on a certain singularity from the Beatles, who lent that quality to everything they touched. (Around the same time, they were inventing music video, pioneering the notion of pop musicians as gurus of their own record label, and — on The White Album — throwing out hot, raw chunks of what would become the rock aesthetics of the ’70s.)

Seen now, the all-you-need-is-love-to-fight-the-Blue-Meanies flower-power fancifulness of “Yellow Submarine” never feels trapped in a late-’60s bubble. That’s because the film is totally ironic about it; it’s such a knowing, joshing, postmodern parable of childlike innocence taking on the forces of destruction that almost every moment in the movie seems to make light of its own existence. Then again, the Blue Meanies really are mean — chirpy allegorical bullies with evil grins who have no master plan beyond the desire to stamp out joy. Whatever era you’re watching “Yellow Submarine” in, you always know who the Blue Meanies are. They’re all around you.

In 1968, feature-length animation that played in movie theaters basically meant one thing — Walt Disney — and it seemed appropriate, and inevitable, that “Yellow Submarine” should be the anti-Disney fable, a teeming counterculture rabbit hole of good and evil, one that was as quippy-punny and crazy-sly as the Beatles’ two live-action features, “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Help!” (the main reason “Yellow Submarine” ever got made, according to John Lennon, is that “It was time for another Beatle movie”), and that possessed a visual splendor as psychedelic as it was storybook.The movie’s spirit descended directly from the Beatles, and that meant two things: Every moment in it was about love, and every moment in it was about change. (The Beatles, at that point, were changing their identities with each new album, an odyssey that became the template for more or less every pop star going forward.) “Yellow Submarine,” in its very shape and form, is an orgy of metamorphosis, from the luscious candified utopia of Pepperland, with trees that look good enough to eat, to the industrial gray Liverpool that features a house of surrealist frenzy to the undersea dreamscape ruled by strobe-light fishies and a vacuum creature that sucks up everything around it (including the film itself) to the M.C. Escher-esque sea of holes. Jeremy, the chattering brainiac the Beatles pick up on their journey, is a sidekick so free-associative his goofiness is almost Joycean.

The Beatles themselves grow old, turn into babies, and become Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The song sequences dart along with fantastic eclecticism, from the tear-drop nickelodeon sadness of “Eleanor Rigby” to the squiggly electro psychedelia of “Only a Northern Song” to the mod one-world sing-along ecstasy of “All Together Now.”And then there’s the sequence that can tickle your eyeballs in a way nothing else ever has. As John Lennon sings “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” we see images of John, a maiden on horseback riding into the clouds, and a couple dancing (they could be Fred and Ginger, or any two people who ever loved each other), and the images dissolve before you into an animated scraggle that grows more and more primitive and elemental and transfixing. It’s beauty drawn outside the lines, beauty that spills over the edges of reality. It is, I think, the single most transcendent sequence in any animated film.

The Beatles themselves grow old, turn into babies, and become Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The song sequences dart along with fantastic eclecticism, from the tear-drop nickelodeon sadness of “Eleanor Rigby” to the squiggly electro psychedelia of “Only a Northern Song” to the mod one-world sing-along ecstasy of “All Together Now.”And then there’s the sequence that can tickle your eyeballs in a way nothing else ever has. As John Lennon sings “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” we see images of John, a maiden on horseback riding into the clouds, and a couple dancing (they could be Fred and Ginger, or any two people who ever loved each other), and the images dissolve before you into an animated scraggle that grows more and more primitive and elemental and transfixing. It’s beauty drawn outside the lines, beauty that spills over the edges of reality. It is, I think, the single most transcendent sequence in any animated film.

If life can be just like a cartoon, then the message of “Yellow Submarine” is that life is never static — life is flux, surprise, revolution, the old melting into the new. And no art form is equipped to tell that tale quite like animation. Yet today’s digitally animated features, as good as some of them are, rarely if ever try to fly this high. And I so wish that a few of them would. John Lasseter, in his more than 20-year reign at Pixar, guided that studio with a kind of trademark shiny-plated aesthetic, and produced many wonderful films, but with Jennifer Lee and Pete Docter now heading Pixar, I hope they do more than just take the studio in new directions of diversity, as vital as that mission is. I hope that every so often (or even once!), they follow the lead of a movie like “Yellow Submarine” and burst the boundaries of imagination.“Yellow Submarine” was, and is, an indelible experience. So why didn’t it have more of a direct influence? Simply put, it was too far beyond. There was something in the water in 1968, and a handful of the movies that made their mark then remain sealed in a weirdly timeless time capsule of cinematic whoa-ness. “2001: A Space Odyssey” revolutionized science fiction — and yet few, if any, tried to mimic its metaphysical head-trip grandeur. (Where would you start?) “Rosemary’s Baby” was a domestic demonic horror show that tapped some dislocation in the world’s spirit, and no horror film that came after it could match its disquieting shudder.

And “Yellow Submarine”? It was an eye-popping pinwheel of love-generation incandescence, created by an army of animators working in the spangled oasis of the Beatles’ mystique. Yet what emerged was a singular vision — one that, like the cover of “Sgt. Pepper,” seemed to pack the entire 20th century into a winking mosaic designed to enchant adults and children alike. To see “Yellow Submarine” today is to be reminded that the spirit of the Beatles has never gone away, and that the Blue Meanies will be defeated. It just takes people working as they always have. All together now.

source:variety.com